“Obstinate, Headstrong Girl!”

- Ally Turkstra

- Jan 15, 2025

- 12 min read

Updated: Feb 14, 2025

The Influence of Women’s Literature, the Power of Books, and the Self-Identity of the Victorian Woman

Writer: Ally Turkstra, M.A

I, like so many other women, rediscovered the magic of fiction during the first COVID-19 lockdown in March 2020. The old patterns and comforts of making a pot of tea, finding a comfortable spot, and getting lost in an unknown world through the crisp cream pages of a new novel. Through revisiting old favourites and discovering new ones, literature kept me company while the rest of the world felt so uncertain. As I turned to virtual forms of connection and community, I noticed that women worldwide were experiencing a similar bookish renaissance. In various online communities, young women were making new friends, exploring their sexual identities, and discovering the philosophies of the human spirit. In the almost five years since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the literary world has blossomed to unprecedented heights, and it is a market predominantly driven by women, taking on a new life in a world dominated by virtual engagement and short attention spans. In rediscovering works of fiction, I found myself understanding references in various other cultural productions, questioning my sense of self and, most notably, trying to adopt the strength and confidence often found in the female protagonists I was reading about.

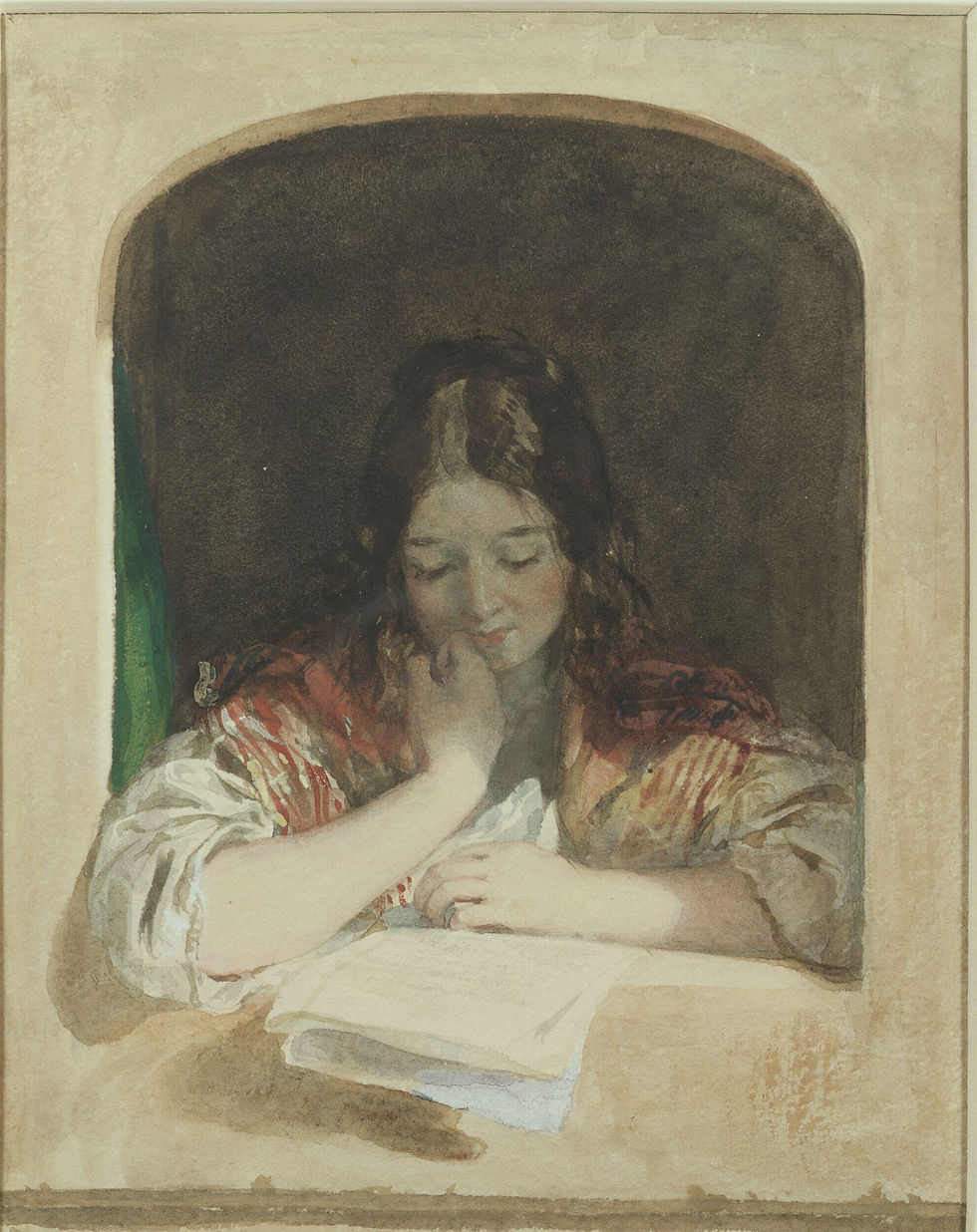

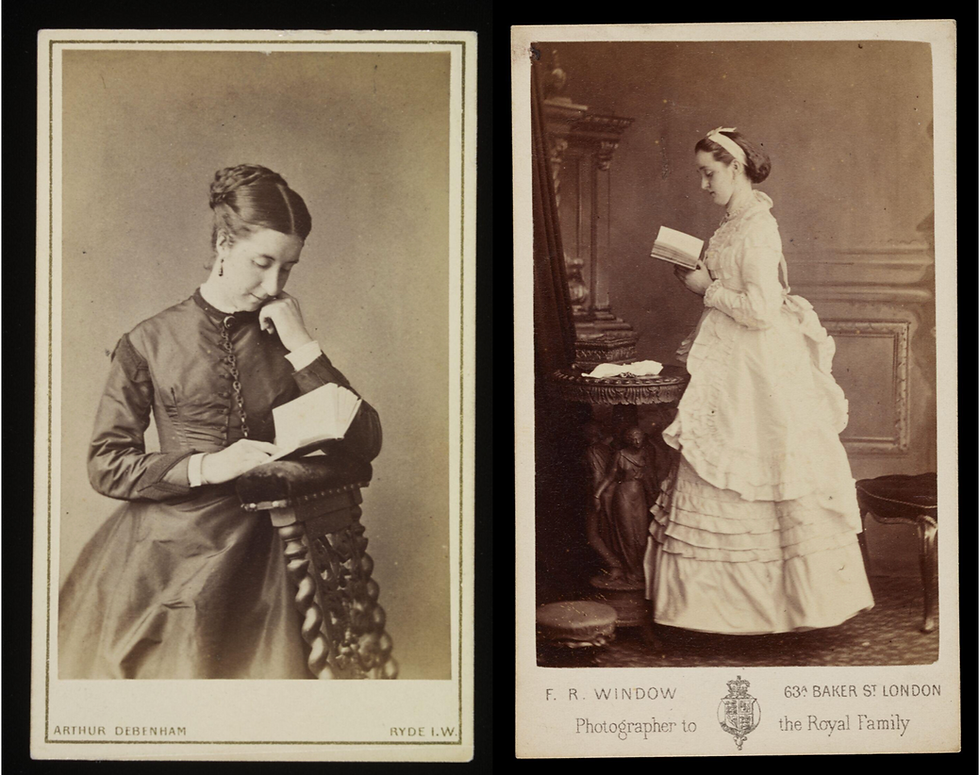

At first, this experience felt exclusively personal and irrelevant to my academic work. However, as I continued my studies of nineteenth-century Britain, I noticed that this profoundly personal relationship to literature that I was experiencing glared back at me through the lives of many Victorian women [1]. By identifying literature as one of the integral heartbeats of the Victorian woman’s life, it also reveals itself as a dominant informant of English culture, consumption, and identity. The industry of written work was acutely shaped and, in turn, shaped by reading women. This history of the well-read woman is not only necessary to understand the socio-cultural evolutions of England in the Victorian period, but it also gives the essential historical context to women’s literary engagement of today. The intimate and intellectual elements of literary engagement are an imperative part of women’s history. Therefore, by tracing this history, we are able to apply a unique lens to the lived experiences of nineteenth-century English women, examining the evolution of the women’s rights movement, engagement with consumerist markets, constructions of femininity and the ideal woman, and female self-perceptions.

By applying literature as a lens to analyze the developing autonomy of the Victorian woman, this article aims to demonstrate how a close examination of women’s literary engagement and literary production provides intimate context to the broader plan of ideological consumption of Victorian Britain. For the purpose of my argument, this essay will be twofold. The first section will take a closer look at a selected collection of literary works that were particularly popular during the mid-to-late Victorian period. With a close analysis of these influential pieces, the sensationalist and romantic fiction motifs reflect contemporary social critiques and how fictional heroines both inspired and were shaped by women engaging with literature. The following section will examine women’s mobilization of literary engagement through personal interpretation and the female authorial voice. By investigating the intimate connection between literature and self-identity in the Victorian period, this section will divulge the relevance of women’s literature in shaping Victorian culture.

The Effect of a Female Protagonist

Various nineteenth-century works, such as Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, and George Elliot’s Middlemarch, exemplify the fictional heroines that inspired nineteenth-century women. In combination with these fiction works, periodical excerpts, magazine articles, and essays also exhibit the influence of literature on women, illustrating the desire for intellectual stimulation, personal inspiration, and escapism. The explosive argument between Elizabeth Bennet and Lady Catherine de Bourgh in Pride and Prejudice features de Bourgh calling Elizabeth an “obstinate, head strong girl” [2]. Their climactic argument centres around the unabashedly vocal and spirited nature of Elizabeth, who embodies a defiance of the social expectations for women in the early nineteenth century. However, it was not until the mid-Victorian period that Austen’s works found real success, as more and more women were drawn to such bold and brazen examples of womanhood.

By the mid-Victorian period, Austen’s work gained popularity as it featured the domestic setting and motif of marriage, which was extremely popular among Victorians. However, the long-standing relevance of such work arguably has more to do with the connection to the complex and relatable female protagonists featured in her work. Despite the attractive setting and emphasis on moral structure, Austen’s work flourished through the complex voices of her female characters, who predominantly applied their wit and intellectualism to assert personal autonomy and equal treatment in public conversation, despite the rigidity of their environment [3]. One of the strongest examples of this is found in the romance protagonist Elizabeth Bennett, who applies her humour as a tool to engage as an equal in social conversation but also presents to the reader a sense of self-expressionist individualism through dialogue [4]. Yet, it is not exclusively in the dialogue of such characters that historians can pull new conceptions of women’s daily life. For example, scholar Nora Gilbert articulates that the popular motif of women running away in nineteenth-century novels, such as Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre and George Elliot’s The Mill on the Floss, contributed directly to the dissatisfaction of restrictive gender roles and contributed to a literary foundation for feminist thought. She argues that through an analysis of strong-willed, run-away heroines, the remote English landscapes of Victorian provincial novels reflect and sometimes contribute to the inner turmoil [5]. By examining a multifaceted collection of narrative elements, Gilbert, in addition to scholars such as Nancy Armstrong and Rebecca Beach, demonstrates the broader historical relevance in breaking down the impetus and subsequent effects of Victorian women’s literary consumption.

In their consumption of varying forms of literature, women explored the written world, thereby enriching their education, perceptions of self, and outlooks on their gendered society [6]. Fiction works written by women or featuring strong female leads allotted for a space in which English women explored new conceptions of gender politics, their roles in society, and their relationship with men. Throughout these novels, female characters are often in charge of dialogue, vocal in social settings, and well-learned. As noted by Nancy Armstrong in her 2005 book, How Novels Think, Armstrong articulates that Austen distinguishes Bennett as a character "capable of shifting the social order" by applying her intellect and personal autonomy [7]. Here, Austen applies a social critique echoing the arguments of Mary Wollstonecraft's proto-feminist work, A Vindication of the Rights of Women; that women should learn to adapt their intellect to prove themselves equal to men in high society [8]. This intersection of proto-feminist theory and fictional inspiration proved to be influential and controversial in Victorian Britain, thereby demonstrating how literature serves as a glimpse into the intimacy of the Victorian woman's lifetime.

Shaping Self-Identity and Victorian Culture

Historians of nineteenth-century Britain have long debated the intimate questions that plagued the personal and cultural experiences of the Victorian woman. What do conceptions of "femininity" tell us about embedded patriarchal systems? What does individuality look like for a woman? Though literature is inherently subjective, contemporary written expression provides unique insight into these more intimate histories. Throughout the nineteenth century, female writers and readers around England used fiction novels as a safe place to explore social critiques, the roles of women, and the impetus of marriage. The necessary propriety and gentility required of Victorian women were restrictive and dominating in many ways; still, literature often provided the path by which one could contemplate one's self-identity, aspirations, and worldview. Though the writing throughout this period ebbed and flowed in its challenge to public society and its emphasis on domestic morality, women were increasingly individualistic due to literary engagement.

The rumination of women's individualism throughout their life is evident through fiction works published in nineteenth-century Britain. Mrs. Henry Wood's 1867 work, Lady Adelaide's Oath, offers a complex critique of the patriarchal structure of high society and its restrictions on women. Namely in its description of Lady Adelaide's relinquishment of her bodily autonomy in getting married, thereby becoming an object of society. Wood's imbued social critique provides a unique insight into women's efforts to present autonomous personhood. The gendered expectations for Victorian women to "maintain their honour" both intellectually and physically established a lack of autonomy. As historian Abigail Boucher puts it, within the bounds of such restriction, women's literature provided a form of consumption that was both tangible and intangible, thereby empowering both a public and a private sense of feminine individualism [9]. Such literary works exemplify the twofold relevance of a literary lens on this history. Namely, how female authors applied their writing as an opportunity to critique the regimented gender roles of English society and the consumption of literature stimulated female readers to engage with social criticisms and challenge the long-standing gendered tropes that governed much of English society.

The newfound popular consumption of literature did not go unnoticed by broader English society, and various public-facing debates occurred regarding such a hobby. Both men and women wrote extensively on the effect of the fictional heroine on well-read women. A periodical from a monthly publication, The Lady's Monthly Museum, featured a debate that contemplated the influence of fiction reading on young girls, questioning if works of imagination were detrimental to young women's minds or encouraged amusement and instruction [10]. The questioning of women's engagement with fiction proves that the imbued social critiques and strong female protagonists were not unnoticed by critics and were defended by women who found inspiration in such pieces. In the periodical, the opinions are diverse, with one orator articulating that reading such pieces "is for the mind what dancing is for the body," and, therefore, harmless. At the same time, the other argued that such frivolity skews the societal comprehension of the fairer sex [11]. The competing perspectives illustrate the traditional, patriarchal tendencies of English society to view well-read women as delusional and the fictional works as the "cause [of] all the indiscretions of youth" [12]. The highly polarizing views toward women's reading habits in the nineteenth century exhibit the nuanced debate between celebrating women's intellectual curiosity and warning against the perceived dangers of excessive or improper reading. Such duality of opinion on literary consumption is a fantastic exhibition of the Victorian period's broader socio-cultural and gendered progressions.

Despite the controversies women's reading caused in society, women continued their literary ventures into novels. Female authors proved inspirational as they represented the opportunity for the publication of the female voice. Still, their characters proved more so, much to the dissatisfaction of publishing gentlemen. In an 1820 book, Female Excellence: Hints for Daughters, by an author just listed as "Mother," there is a concrete examination of the effect of fictional and romance literature on young women. Though there are many patriarchal tendencies in this piece, such as the assertion that novel reading may fill a young woman's mind with nonsense, the author does not shy away from the individualistic inspirations born out of strong female characters [13]. Focusing specifically on self-determination, the author promotes novel reading to young women not just because of its potential to improve manners and sensibility but also for the encouragement found in literary works for women to act as their own agent, to have power and choice over the decisions they make, particularly in romance [14].

The mediated individuality that well-read women established, affected both their roles in public and private life. Self-governance and personal autonomy were prominent features in female protagonists of popular fiction literature. They inspired the individual young lady to consider herself an active member of society and for a wife to consider herself an equal in a marriage. Featured in the Lady's Pictorial, Miss. Emily Faithful wrote that women in marriages were often bound to a mitigated world of domesticity where their husbands possessed much social freedom [15]. In an article in the Derbyshire Times and Chesterfield Herald, Miss. Faithful's assertions are contemplated. The article argues that it is not only the bounds of domesticity that restrict women from realizing their full societal potential, but their lack of literary engagement as well [16]. Faithful argued that a woman stays in touch with the world around her through newspaper reading where a novel inspires the spirit [17]. Faithful's work is particularly relevant in her discussion of the intimacy of literary engagement for women by, most notably, the piece emphasizes that a woman's lesser societal engagement is not whatsoever due to her inadequateness, but instead is a result of the society she exists within [18]. Faithful's work is a brilliant primary source representation of the innermost importance of literature and the woman's social confinements, exemplifying the vitality of using a literary lens to explore women's history.

Conclusion

There is something deeply personal about studying the history of women’s literature. The intimacy of literary culture has so intrinsically informed my life and work, and to know such a profound experience is felt by women centuries apart makes my historical work feel so much more tangible. Though the experiential planes differ, the soul-deep relevance of literary culture remains the same across centuries, and Victorian women’s experiences are but a small example. Applying this kind of literary history to explore the intimacies of womanhood is very relevant to furthering the nuances of social history, as well as providing a historically founded backbone to much of the present-day cultural production that affects the ongoing work for women’s rights. As this essay has exhibited through a close analysis of the literary material in question and its effect on nineteenth-century English women’s self-identity and social culture, this history is not only fundamental to enriching and personalizing the histories of English women who are often left in the peripheries of social history but also provides intimate context to the broader plan of ideological consumption of Victorian England.

In their 2024 release, Social Reading Cultures on BookTube, Bookstagram, and BookTok, authors Bronwyn Reddan, Leonie Rutherford, Amy Schoonens, and Michael Dezuanni state that "reading is an inherently social practice… a dynamic activity that produces meaning shaped by the time, emotion, and place in which a reader reads" [19]. Reddan and their coauthors articulate this argument in the context of the literary culture I am a part of, where it is as much about the engagement with literature as it is about the public identity of bookishness. Young women on platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube apply their literary engagement as an aesthetic identity as much as a continuous journey of intellectual stimulation. They become the "literary sponsor;" a consumer who facilitates and controls literacy and benefits from doing so, thereby emphasizing the transformative power of books [20]. Though the platform that Reddan and co. apply in their analysis is a product of the twenty-first century, the transformative nature of books, the communities that foster them, and the inspiring narratives in women's literature is a centuries-old practice. If Guy de Maupassant is right and "black words on a white page are the soul laid bare," I suspect Emily Faithful's 1893 words will continue to endure, and literature will remain an imperative element of women's history.

Endnotes

[1] The Victorian Woman that is discussed in the following essay is predominantly of the middle/upper-middle class. There is variety in experience when it comes to the working-class women and their literary engagement, as is there for genteel women.

[2] Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice. (Cambridge University Press, 2006): 394.

[3] Examples of these protagonists are, Austen’s Elizabeth Bennett and Emma, Wood’s Lady Adelaide, and Evans’ Dorothea Brooke.

[4] Rebecca Beach, “Turning Their Talk: Gendered Conversation in the Nineteenth- Century British Novel” (PDF, University of Kentucky, 2015): 33 & Nancy Armstrong, How Novels Think: The Limits of British Individualism from 1719-1900 (Columbia University Press, 2005): 4.

[5] Nora Gilbert, Gone Girls, 1684-1901: Flights of Feminist Resistance in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth-Century British Novel, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2023): 13.

[6] Sensation fiction was a popular literary genre in the 19th century. The novels often featured motifs of the Industrial Revolution and gothic romance. More notably, the genre was dominated by female authors

[7], Nancy Armstrong, How Novels Think: The Limits of British Individualism from 1719-1900 (Columbia University Press, 2005: 4.

[8] Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (Yale University Press, 2014): 135.

[9] Abigail Boucher, "Incorporeal and Inspected: Aristocratic Female Bodies and the Gaze in the Works of Mrs. Henry Wood," Women's Writing 28, no 1 (2021) :93.

[10] Debate for the Ladies. Lady’s Monthly Museum. Pg. 132.

[11] Ibid, 133. The term “fair sex” or “fairer sex” was common in 19th century vernacular to describe women and mainly upper-class ladies.

[12] Ibid, 133.

[13] Female, Female Excellence; or, Hints to Daughters, by a Mother (Fisher Son #38; Co., 1838): 13.

[14] Ibid, 9.

[15] "Employment of Women." The Lady's Newspaper & Pictorial Times (July 7, 1860): 12.

[16] "Women and News Paper-reading." Derbyshire Times and Chesterfield Herald (September 23, 1893): 6.

[17] Ibid, 6.

[18] Ibid, 6.

[19] Bronwyn Reddan, Leonie Rutherford, Amy Schoonens, and Michael Dezuanni. Social Reading Cultures on BookTube, Bookstagram, and BookTok (Oxford: Taylor & Francis Group, 2024.): 1.

[20] Ibid, 3.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Austen, Jane. Pride and Prejudice. Cambridge: Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

"Debates for The Ladies." The Lady's Monthly Museum, March 1, 1807, 132+. Nineteenth Century UK Periodicals.

Female. Female Excellence; or, Hints to Daughters, by a Mother. Fisher Son & Co. 1838.

Wollstonecraft, Mary. A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Yale University Press, 2014.

"Women and News Paper-reading." Derbyshire Times and Chesterfield Herald, September 23, 1893, 6. British Library Newspapers.

Secondary Sources

Armstrong, Nancy. How Novels Think: The Limits of British Individualism from 1719-1900. New York: Columbia University Press, 2005.

Beach, Rebecca. “Turning Their Talk: Gendered Conversation in the Nineteenth- Century British Novel.” Dissertation. University of Kentucky, 2015.

Boucher, Abigail. “Incorporeal and Inspected: Aristocratic Female Bodies and the Gaze in the Works of Mrs. Henry Wood.” Women’s Writing 28, no. 1 (2019): 90–106.

Gilbert, Nora. Gone Girls, 1684-1901: Flights of Feminist Resistance in the Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century British Novel. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2023.

Reddan, Bronwyn, Leonie Rutherford, Amy Schoonens, and Michael Dezuanni. Social Reading Cultures on BookTube, Bookstagram, and BookTok. Oxford: Taylor & Francis Group, 2024.

Comments