“The Legacy of Being Queer. Love. Radical Love.”

- Meghan Dudley

- Jun 14, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Jul 15, 2025

What Does Stonewall Mean to Us and Queer Heritage Today?

Writer: Meghan Dudley, Ph.D

Introduction

I distinctly remember the first Pride parade I ever attended, which was in Oklahoma City on September 26, 2021. As a newly out cis-bisexual, polyamorous woman going to graduate school in Norman, Oklahoma, I was so excited to celebrate with my closest friend and one of my partners at the time. Both of them came over to my apartment to get ready, decked in their Pride-rainbow finest. At the time, I had exactly one rainbow shirt from a local business that I wore with bi-colored eye shadow (which, as my chapstick-femme self, I had plenty of help applying). We loaded up the car with camp chairs, umbrellas for shade, and sunscreen for a hot fall day in Oklahoma and drove the 45 minutes to Oklahoma City’s 39th Street, the city’s historic gaybourhood where the parade took place. We took up our seats on a rise overlooking the main part of the gaybourhood and proceeded to cheer ourselves hoarse as floats from local community groups, supportive churches, and businesses rolled by. I remember it being an exhilarating day— my first chance after COVID to be out in the community, and our community’s chance to celebrate Pride, as well as to remember Stonewall.

For many of us queer folx, the Stonewall riots that took place in the summer of 1969 on Christopher Street in New York City loom larger than life in our community’s understanding of queer history and heritage. I know, for me, it occupies such a central part of my sense of queer history that I cannot honestly say when I first learned about Stonewall; it seems like I have always known about it. If you were asked to give an accounting of Stonewall, it might go something like my own summary: BIPOC transwomen, like Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, along with countless other queer folx fought back against the police raids by rioting for several days around June 28, 1969 at the Stonewall Inn. Although not the first queer protest against police brutality, Stonewall was different for the national headlines it inspired; for the first time, queer issues made national news and entered the national consciousness. A year later, on the anniversary of the riots, activists organized the first march that would inspire Pride parades and the movement around the country. Pride festivals and parades 56 years later reflect more of a celebration of queerness than a protest, but many in the community are quick to remind folx that Pride was first a riot.

I think we can all agree that Stonewall is not only an important part of queer history, but of queer heritage as well. I follow the definition of scholars David Harvey (2008) and Alicia Marchant (2019), who describe heritage as an affective or emotional relationship in the present between people living today and those people, places, things, and events that came before us to shape the world in which we live. Because of its important role in queer history, Stonewall has become larger than life: a part of queer history and a heritage symbol of queer liberation as much as it was a historical event. And as a symbol and a part of our queer heritage, its meaning can change and vary based on the individual’s relationship with it and what it represents to them. In the 56th year since Stonewall burned its way into our collective memory, it makes me wonder: what does Stonewall’s legacy mean to us as queer folx today? Do we all think about it the same way? Or does it mean something different to the diverse pockets of the queer community across the United States?

I suggest that we can answer this question through my dissertation research, which studies queer heritage as an archaeologist at the University of Oklahoma. As an anthropologist and archaeologist, I study the past not through primary documents like a historian, but by talking to people of today, visiting and observing communities and places today, and analyzing objects or artifacts that tell someone’s story. Through these everyday artifacts and experiences, anthropologists and archaeologists piece together a story of the past. My research, along with its public-facing component, the Rainbow Community Heritage Project (RCHP) (@rainbow.chp), aims to highlight and give voice to queer heritage, particularly in areas outside of cities like San Francisco and New York, through the tools of anthropology and archaeology.

My dissertation and its associated RCHP consist of two primary methods. First, I used a qualitative, 15-minute survey through RCHP to build the publicly available digital community archive. This survey invited participants to identify an object (or artifact) in their own lives that represents their queer story and answer a few questions about it. The survey, though primarily aimed at folx in Oklahoma and other conservative states in the United States, was made available nationwide. Anyone 18 years or older and queer-identifying could take the survey and share their artifact with the project. The results of the survey and people’s contributions can be seen on RCHP’s website, with a participant’s permission. Second, I conducted 27 ethnographic, object interviews with queer folx in Oklahoma. Like the survey, interviewees selected an artifact from their personal lives to discuss in a 20 to 90-minute, unstructured, ethnographic interview. In addition to preserving queer artifacts and stories, the survey and interviews aimed to understand how folx living outside major urban centers connected to queer heritage, and how their personal artifacts and stories fit into the larger tapestry of queer history.

For this article, I reflected on my dissertation data with the Stonewall riots in mind. When asked what came to mind when they thought of queer history, nearly all interview participants (n = 20) referenced Stonewall, but few talked about it at any length. There were, however, three individuals who did, and their responses can give us some insight into what Stonewall might mean for many of us.

The Stories

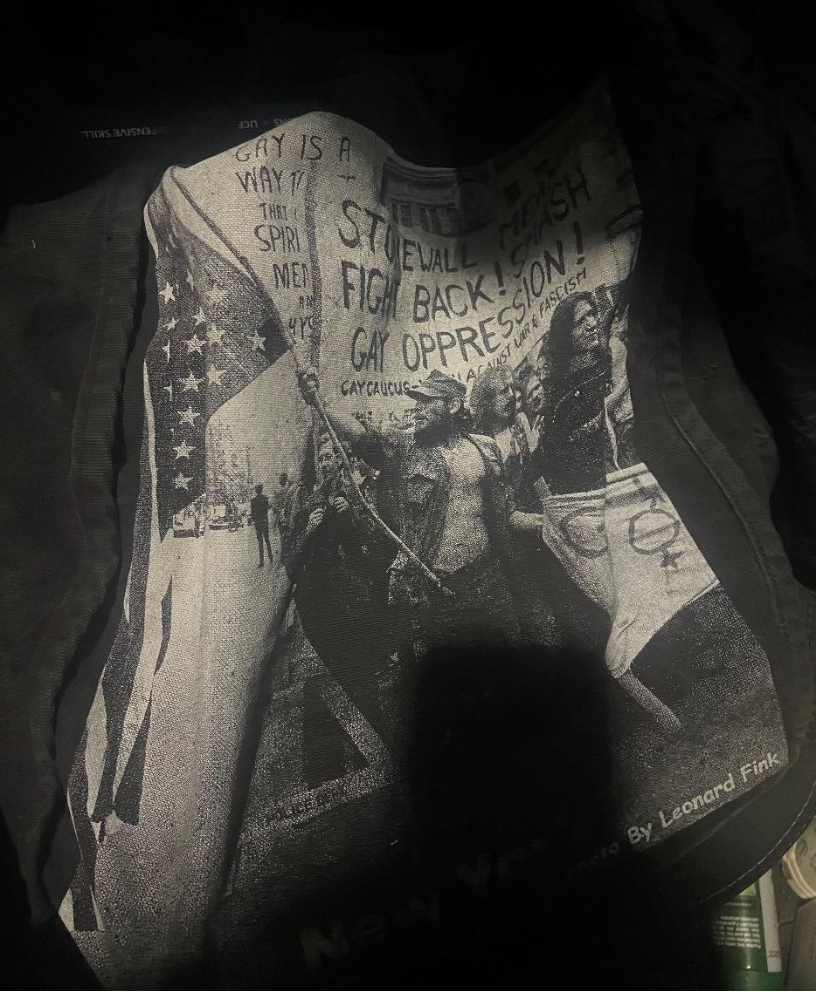

Many participants viewed the events that happened at Stonewall Inn as a symbol of queer resistance in history. Their perspectives are best represented by one millennial, bisexual, non-binary participant from Colorado. For them, Stonewall inspires their own queer activism and resistance today. Contributing through the RCHP survey, this person shared a tote bag they purchased at Stonewall Inn (Figure 1):

I got this bag while on a trip to New York City in 2013. I had just realized I was bisexual when I got it and to this day and it reminds me consistently of the importance of queer community and resistance. […] I have taken this bag with me all over the country and currently use it as my bag for my instruction manual when I teach driver’s education. I want queer students who either [see] the Stonewall label on the back or the image of gay protesters on the front to be able to know they aren’t alone. It’s vital for queer youth to know that there have been generations before them who have fought for them, and see adults who have the courage to be seen right now (Survey 21, 9 January 2024).

Purchasing this tote bag was no simple souvenir we might collect to remember a vacation. For this person, this artifact serves as a daily reminder to themselves and those around them of the value of queer resistance. Stonewall left a legacy that beckons them to follow in their elders’ footsteps.

As a community response to policy brutality and harassment, the Stonewall riots serve as a symbol for themselves and those around them, particularly students, that our community was historically forged through resistance and the solidarity that binds us together.

In contrast, for some folx, like one millennial, pansexual, non-binary survey participant from New York, Stonewall is an event that touched their lives in a personal way. In their survey response, this participant shared a framed quote from their cousin as their chosen artefact, which sits on their meditation altar at home. It reads: “Love your fucking life. Take pictures of everything. Tell people you love them. Talk to random strangers. Do things that you’re scared to do. Fuck it, because so many of us die and no one remembers a thing we did. Take your life and make it the best story in the world. Don’t waste that shit” (Figure 2).

When asked to describe their artifact, this is what the participant wrote:

A framed quote about “Living Your Fucking Life” was given to me by my familial queer icon, my cousin Vinny (yes, really). Vinny is an HIV/AIDS survivor who is one of the only surviving members of his friend group from Stonewall. It reminds me every day that we only have today to be as fulfilled and happy as possible. Live out loud in queer joy is his message to me and to everyone. That framed quote is my daily reminder. […] Vinny made the quote and frame for himself as his own reminder and tribute to Stonewall friends of his lost to AIDS. I was struggling with my own identity and how my family reacts to me. He decided to pass along the framed quote to inspire me, the future generation, to inherently be unapologetic about living your true authentic life (Survey 4, 11 April 2023).

For this person living in New York, Stonewall is not an abstract symbol or historic event; it is personal and alive within their own family member. Vinny, a Stonewall participant and an AIDS survivor, embodies these historical events and their impacts on our community in a very real way for this participant, as someone they love. Their framed quote, then, is a tangible link between the participant and their cousin – and, by extension, Stonewall.

While Stonewall continues to be a symbol of queer resistance and community, especially for those with personal connections to the event, for some, learning about Stonewall came later in life. One lesbian elder I spoke to in Oklahoma did not even learn about Stonewall until decades later, by working with queer youth. In her interview, she described how she first learned about the Stonewall riots:

[T]hey were the ones that taught me about, you know, uh, Marsha P Johnson and Sylvia Rivera and, um, and even Stonewall and just, um, it was so incredible to me. […] But they were also like the first that, they also got me on Myspace and almost got me divorced early on. But that's another story! But I guess they were their first generation that was really online, and they could do all the researching and look up all the stuff (Interview 8, 23 June 2023).

The internet has radically changed our community in the ways we communicate and how we remember our past. For our elders who did not grow up with the internet as younger generations have, especially those outside of major metropolitan areas, Stonewall happened out of sight, out of mind. Instead, queer history and heritage to this participant was local. When asked what queer heritage meant to her, she only referenced Stonewall for a few seconds but spent a couple of hours detailing local Oklahoma queer history. For our elders, the Stonewall riots were one of many local events around the country that showcased queer resistance and activism—and it is the local events that directly touched their lives that matter.

Conclusion

Even from these three examples, we can see that Stonewall has a wide-ranging legacy on our community,—from acting as a symbol for queer resistance and community, to an event that personally touched people’s lives, to being another event in another community among many. And these are only three examples! For myself, as someone who came out as queer in Oklahoma, Stonewall feels like a monument to queer resilience and resistance that I aspire to visit one day, much like a pilgrimage. It might mean something entirely different to you, dear reader. Regardless of what your relationship to Stonewall might look like, its impact on queer history and how we relate to it through heritage continues to echo across time. Its legacy and queer heritage in general might best be summed up by the New York participant:

Heritage can be grounding. It’s so important to know who came before you and gave you the rights you have now. Our queer ancestors fought, died, were abused, neglected, ostracized all so that we can live a freer life. They loved us before knowing us. I think that’s the legacy of being queer. Love. Radical love for our queer family members everywhere. Whether we know them, have even met them, or not (Survey 4, 11 April 2023).

Happy Pride!

Queer Vocabulary

Bisexual: a sexual orientation in which an individual is attracted to two or more genders

Cisgendered: an individual who identifies with the gender assigned to them at birth

Folx: the inclusive term for “folks,” used to acknowledge the diversity of gender expressions in queer community

Non-binary: a gender identity in which the individual does not identify within the gender binary of male and female

Pansexual: a sexual orientation in which an individual is attracted to another regardless of gender

Polyamorous: a relationship orientation on the ethical nonmonogamy spectrum, in which an individual is capable of having multiple romantic relationships simultaneously

Queer: originally a 19th and 20th century slur against members of the LGBTQ+ community, this reclaimed word now broadly represents sexual orientation and (or) gender identities outside of the cisgendered, heteronormative standards of Western culture

Acknowledgments

Dissertations, like children, need a village to be “raised” in – and mine has certainly benefited from the best village a graduate student could ask for. First, thank you to Dr. Bonnie Pitblado and the Oklahoma Public Archaeology Network for supporting my work and giving me the space to create this project. Second, a huge thank you to OKPAN interns for all the hours you have put into this project: Lauren Jablonski (she/her), Jace Hill (he/him), Jovie Taylor (they/them), and Isabella Rosinko (she/her). I would not have survived this without your help! I also want to thank one of my partners, Ameris Poquette (she/her), for creating the RCHP logo. I also want to thank the Oklahoma Anthropological Society and the LGBTQ+ History Association; you ensured my research and fieldwork thrived, and I am so grateful for your support. Finally, but certainly not least, I am so grateful to the community members who have supported this project through surveys, interviews, and (or) your words of encouragement and support. I could not have gotten here without y’all! Thank you! (This research was conducted under IRB No. 15699).

Bibliography

Harvey, David C. 2008 The History of Heritage. In The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity, ed. B. Graham and P. Howard, pp. 19-36. Routledge, New York.

Marchant, Alicia (ed.). 2019. Historicising Heritage and Emotions: The Affective Histories of Blood, Stone, and Land. Routledge, New York.

Comments