Eat Your Heart Out

- Marienza Miserere

- 17 hours ago

- 11 min read

The Representation and Role of Food in Love and Lust

Food history is an extremely fascinating area of study. What did people eat and why did they eat it? There are many different aspects of studying food history, like customs, cultures, traditions, nutrition, tools and technologies, recipes, and even the service industry. As an urban historian, the latter is the most fascinating to me. I don’t really study what people eat, but I do look at how food-related sites and careers are important to cities as well as their social growth and physical development. Restaurants and diners were not just places to eat, but were also sites of organized protest or impromptu rioting, like the planned forty-student sit-in at Woolworths’s “white’s only” lunch counter in Nashville [1], and Compton’s Cafeteria Riot in San Francisco [2]. They were also sites of community and kinship, where people would gather in groups to share a meal or a cup of coffee. Places like Chinatowns and a city’s “Littles” (like Little Italy, Little Portugal, Little Jamaica, etc.), in addition to the history of grocers, mongers, and street food stalls, are all central ties between food and immigration history that shape metropolitan spaces.

Returning back to food itself, the kinds of food people ate, depicted, and wrote about can also tell us a lot about society. Food can tell us about our taste, culture, traditions, and even biases, locality, and adaptability. Think about what a 1930s Great Depression meal, or a war ration pack, or even the use of SPAM in East Asian cuisine says about things like the economy, technology, agriculture, and transnational cultural influence. Think about colonization, consumerism, slavery, and industrialization; the spice trade, coffee, mass production, sugar cane, canning, and refrigeration. Food has impacted and reflected the people who make and consume it for a very long time. So, with this at the forefront of our minds, let’s look at the tie between food and emotion.

How is food representative of our feelings?

For this article, and its timely publication on Valentine’s Day, we’ll be looking at the role food plays in romance. Today, people might associate strawberries, cherries, candy hearts, and lollipops with the celebration, but what are some other romantic foods according to history? Together, we’ll be sifting through Greek and Roman myths, some Caravaggio paintings, and some twentieth-century advertisements and poetry to cobble together a few more foods and drinks people have associated with love and desire. And maybe by the end, you’ll have a better understanding of what you should be eating this Valentine’s Day, at least, according to some people in the past.

Apples

There are many idioms, proverbs, and phrases that correlate food to emotion, love, and sexuality: “Eat your heart out,” “apple of my eye,” “the way to a man’s heart is through the stomach,” “eat your feelings,” and perhaps a more obscure interjection, “Dip me in honey and throw me to the lesbians,” which deserves a revival in the current vernacular. It’s in these sayings, that we find the first fruit we’ll be examining.

Apples may not be the most love-related fruit you can think of, at least not before strawberries, figs, or cherries. As for Greek mythology, the first fruit you may think of is pomegranates, tied to stories of Persephone and Hades’ relationship. But apples have their fair share of appearances across Greek and Roman myth and epics, like in the eleventh labour of Hercules and in love stories. In this section, we’ll look at two stories of, specifically, golden apples, and their association with Aphrodite or Venus, the Goddess of Love.

In one story, The Judgment of Paris, an apple began the Trojan War. Eris, the Goddess of Discord (sometimes rivalry or chaos), was said to have rolled a golden apple into a wedding that she was not invited to [3]. It landed at the feet of Paris of Troy, a human prince, and inscribed into it were the words “To the Fairest.” Now, he had to choose who to honour. Give the apple to Hera, and she offered him land (in some stories youth). Give the apple to Athena, and she offered fame. But Aphrodite bribed him with an offer he couldn’t refuse — the most beautiful woman to be his bride. Paris gave Aphrodite the apple, and she fell him into love with Helen, a woman already married to Menelaus, King of Sparta. Thus, begins the events of the Trojan War [4]. In this context, the apple signifies many things, like chaos, contest, beauty, and in our reading of it, the spoils of love, or at least desire, yearning, and promise.

Golden apples appear again in Ovid’s Metamorphoses [5]. Moving into Roman mythology, Ovid writes the story of Atalanta. In the myth, Hippomenes prays to Venus (Aphrodite’s Roman counterpart) to help him win over the very beautiful Atalanta, whose condition for marriage was to beat her in a foot race. However, if the suitor loses the race, he would die. Atalanta was the fastest runner in the land, and to beat her would have been impossible. To help Hippomenes win the race, Venus provides him with three golden apples to drop in front of Atalanta to slow her down. In hopes of distracting her enough to win the race, Hippomenes threw the apples and as planned, Atalanta stopped to pick them up. But on the third apple, she hesitated with the finish line up ahead. Venus then uses her powers to encourage Atalanta to retrieve the fruit, and Hippomenes wins her hand in marriage. Again, we see the golden apple signifying contest and desire. We see these apples as Venus’ blessing and Atalanta’s course being physically altered by love.

There is a field there which the natives call

the Field Tamasus—the most prized of all

the fertile lands of Cyprus. This rich field,

in ancient days, was set apart for me [Venus],

by chosen elders who decreed it should

enrich my temples yearly. In this field

there grows a tree, with gleaming golden leaves,

and all its branches crackle with bright gold.

Since I was coming from there, by some chance,

I had three golden apples in my hand,

which I had plucked. With them I planned to aid

Hippomenes. While quite invisible

to all but him, I taught him how to use

those golden apples for his benefit [6].

Grapes and Wine

Still in the realm of Greek and Roman myth, we’re moving to the Renaissance. Part of the ‘rebirth’ was the interpretation and appreciation of the classics, like philosophy and mythology. Renaissance painters would often find inspiration in the stories of gods, goddesses, and heroes. It is in this time period when we get some of the most famous Venus paintings like Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (1485/1486) and Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1538). For this section we’ll be moving away from Venus, and looking at Bacchus, the God of Wine, specifically Caravaggio’s Bacchus (1598) and related paintings [7].

Bacchus by Caravaggio was an oil on canvas painting. It depicts a young man, semi-nude, wrapped in a toga. He’s wearing a crown of grape leaves, toying with his drawstring belt while his other hand holds an outstretched wine glass. In front of him, is a decanter and a bowl of fruit. If you look closely enough you might be able to make out a variety of fruits, including some of which have already been mentioned in this article, like a cracked-open pomegranate, apples, figs, pears, and a peach or apricot. The fruit that we’ll be focusing on are the grapes in the form of fruit, leaf, and wine.

Bacchus was part of an early series of paintings done by Caravaiggio that depicted men and fruit. These include Young Sick Bacchus (1593), Fruttaiolo (Boy with a Basket of Fruit, 1593), Fanciullo Morso dal Ramarro (Boy Bitten by a Lizard, 1593), and Boy Peeling Fruit (1593). Fruttailio and Franciullo both depict a similar looking man, with their right shoulder exposed and curls of dark hair. However, while Fruttailio holds a basket, Franciullo is only shown with cherries, and unlike the others, white flowers. Young Sick Bacchus is the earliest in the series, and was a self-portrait depicting Caravaggio while he was ill and recovering from malaria. When it comes to the fruit in Young Sick Bacchus, the Borghese Gallery writes that “...the fruits are much better depicted [in Fruttailio and Franciullo], which undoubtedly shows the improvement of Caravaggio’s condition both physically and mentally”[8].

In Bacchus, but likewise in Young Sick Bacchus and Fruttailio, grapes are abundantly present. Of course, this is not surprising for the God of Wine, but Fruttailio is not said to be Bacchus. There is a sensuality in the paintings: the ripe grapes, the exposed skin, the

bountifulness. Both Bacchuses feature the toga’s drawstring prominently, with one on the table and one being held. Bacchus and Fruttailio’s figures are both flushed and are lit rather romantically. In Bacchus, not only is his toga draped off of him, but the abundance of material around him evokes something more like bedsheets, and the wine glass welcomes you to sit with him. His crown of grape leaves is likewise indicative of sex and desire, as grape leaves are often associated with fertility, rebirth and youthfulness. Perhaps, even a symbol of the Renaissance and virility. In this context then, the grapes are not only sweet and ripe, but also intoxicating and addictive. They are a fruit of lust and passion, and the wine that coaxes you to lose your inhibition.

Chocolate

The last section of this article will look at something more classically associated with Valentine’s Day: chocolate. Whether you’re dipping strawberries in it or gifting a box of it to someone you love, chocolate is central to many Valentine’s marketing campaigns. Perhaps one of the most versatile sweets, advertised at Halloween, Christmas, Valentine’s Day, and Easter, it seems to be wherever you go, taking up grocery store shelves every season. From ads, to greeting cards, and poems these last few paragraphs will look at the association of love and chocolate.

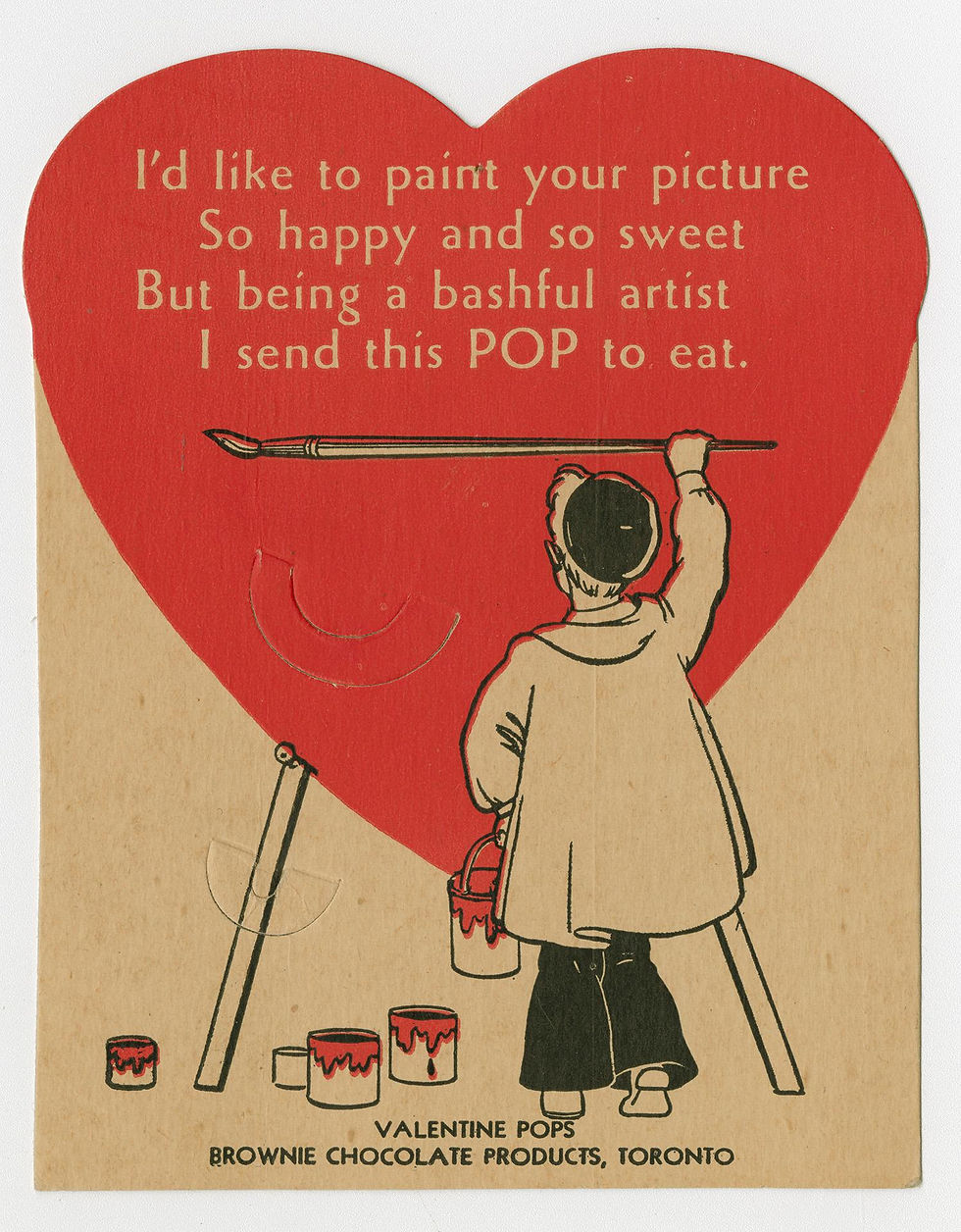

A 1941 advertisement for Jell-O Pudding read: “What do you want most in a chocolate dessert? Rich flavor, of course—a luscious, deep, old-time chocolate taste. That’s what gets you kisses and compliments” [9]. A February 1965 chocolate cake magazine recipe said, “Make it often [the chocolate cake] -- whenever you feel in a valentine mood” [10]. In the 1940s, chocolate was on US government rations, and it was impacting Valentine’s Day traditions according to the New York Times. “Chocolate, as you know, is in short, and manufacturers are not only allotted less of the stuff than they were last year, but they are also forbidden to make fancy forms such as hearts out of their small supplies,” the paper wrote in 1942. “As a result, some confectioners are trying to ‘stretch’ the precious material as far as possible, by assigning their chocolates to smaller containers. One store in Manhattan actually limits its customers to a pound purchase”[11]. Not having chocolate for Valentine’s Day was an outrage! How else were they going to show their love, if not with heart shaped, two pound chocolates? Hard candies were their solution, peppermints, cinnamon sticks, and sour balls, apparently. Companies were also making greeting cards to go along with these candies. In the 1930s, Brownie Chocolate Products in Toronto, Canada, produced a series of lollipop greeting cards for the occasion [12].

When it comes to chocolate and the expression of love and lust, we can also find examples of twentieth-century poetry that plays into this association, like “Dreamscape of the Margin.” In this provocative poem published in a queer zine, Figment Fragments, an anonymous contributor wrote about the sexualization and eroticization of chocolate. The poem begins with, “Mama told me sex was like hot chocolate, not hot cocoa. She and mom were Godiva in bed, not Swiss Miss,” and goes on to say they “ran away from home searching for my own Godiva”[13]. The poem explicitly imagines chocolate in erotic scenarios of pleasure and fantasy, linking the confectionary to body, desire, and intimacy. This tie to sexuality, however, isn’t novel.

In Women’s Conflicts about Eating and Sexuality: The Relationship between Food and Sex, authors Meadow and Weiss quote various women on their relationship with chocolate. In numerous accounts, many regard the experience of consuming chocolate as sensual and even sexual. One woman, Mira Stout in a 1986 Vanity Fair publication compares, “melt-in-the-mouth statements about chocolate to falling in love, and presents the theory that phenylethymine, a natural ingredient in chocolate, simulates the hormonal effects of being in love [14].” Another woman was cited as saying, “Chocolate ice cream is not something I like. It is something I love, like having an affair. I do it secretly and in bed” [15].Meadow and Weiss explain that when food and eating become sexualized, they are not only given the power to arouse but also a sense of moral power. They then liken the act of binge eating to self-pleasure, and the moral implications of feeling dirty afterwards. Chocolate and sexuality then have a much more complex relationship than perhaps perceived on the surface. While gifting chocolate to a sweetheart is a yearly February 14th tradition, the consumption, eroticization, and enjoyment of chocolate has been linked more deeply to expressions of love and lust.

***

Food history is fascinating, isn’t it? The way people write, depict, and speak about food as metaphor, allegory, and simile is an interesting area of exploration. Throughout this article we looked at apples as love in mythology, grapes and wine as sensuality in Renaissance paintings, and the complex identity of chocolate from consumership to sexuality. But there are many more foods to explore, and sources to draw from. One could write an entire book on this very topic in an interdisciplinary look at film, literature, art, music, and poetry. Together, we’ve seen how food and eating has been used as a motif and symbol to represent something more than nutrition. In these instances, food takes on a different life, not as sustenance, but as emotion. So, this year when you gift fruits, wine, chocolate, and candies, think about why those are the common gifts of love and affection, and not only how they are standardized gifts for a capitalist holiday, but how they represent human emotion.

Endnotes

[1] For more information read: Robert Darden, “The Sit-Ins,” in Nothing but Love in God’s Water, 11-22, (Penn State University Press, 2017): 13.

[2] For more information read: Susan Stryker, Transgender History

[3] Although there is no one place to find this myth, it was spoken about in this play: Young. W. W.. The Judgement of Paris! Nonpareil Printing Co., 1877.

[4] For more on the Trojan War, read Homer’s The Iliad.

[5] Ovid’s Metamorphoses.10.560. https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0028%3Abook%3D10%3Acard%3D560

[6] Ibid.

[7] Patrizia Naldini, “Bacchus by Caravaggio,” Uffizi Galleries, https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/caravaggio-bacchu

[8] “Young Sick Bacchus by Caravaggio,” Borghese Gallery Rome, https://borghese.gallery/collection/paintings/young-sick-bacchus.html

[9] Parkin, Katherine J. Food Is Love: Advertising and Gender Roles in Modern America, (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007): 49.

[10] I-love-you CAKE: CHOCOLATE CAKE '65. (1965, 02). Seventeen, 24, 144-145, 148.

[11] J. H. “News of food: Valentine loses her chocolate heart, but there are goodies to console her,” New York Times, (1943, Feb 11).

[12] For more on the interesting history of consumerism and chocolate in Canada, read: Janis Thiessen, “The ‘Romance’ of Chocolate: Paulins, Moirs, and Ganong,” in Snacks (Canada: University of Manitoba Press, 2017). https://digitalarchive.tpl.ca/objects/382097/id-like-to-paint-your-picture? https://digitalarchive.tpl.ca/objects/382098/im-humpty-dumpty-on-a-wall?

[13] Anonymous, “Dreamscape of the Margin,” Figment Fragments no. 2 (Date Unknown). https://www.digitaltransgenderarchive.net/files/gt54kn24n

[14] Rosalyn Meadow, and Lillie Weiss. Women’s Conflicts about Eating and Sexuality: The Relationship between Food and Sex. (New York: Haworth Press, 1992): 20.

[15] Ibid, 20.

Bibliography

Art and Images

Bacchus, Caravaggio

Young Sick Bacchus, Caravaggio

Boy with a Basket of Fruit, Caravaggio

Boy Bitten by Lizard, Caravaggio

Boy Peeling Fruit, Caravaggio

“I Like to Paint Your Picture (Valentine’s Greeting Card).” Brownie Chocolate Products, 1930s. Courtesy of Toronto Public Library. https://digitalarchive.tpl.ca/objects/382097/id-like-to-paint-your-picture?ctx=7d5016824521564d30b7d246c7654b91c87306b2&idx=22

“I’m Humpty Dumpty on a Wall (Valentine’s Greeting Card).” Brownie Chocolate Products, 1930s. Courtesy of Toronto Public Library. https://digitalarchive.tpl.ca/objects/382098/im-humpty-dumpty-on-a-wall?ctx=7d5016824521564d30b7d246c7654b91c87306b2&idx=23

Primary Sources

Ovid. Metamorphoses. 10.560. Translation by Brookes More. Boston: Cornhill Publishing Co. 1922

Young. W. W. The Judgement of Paris! Nonpareil Printing Co., 1877.

Anonymous, “Dreamscape of the Margin,” Figment Fragments no. 2 (Date Unknown).

“I-love-you CAKE: CHOCOLATE CAKE '65.” (1965, 02). Seventeen, 24, 144-145, 148.

J. H. “News of food: Valentine loses her chocolate heart, but there are goodies to console her,” New York Times, (Feb 11, 1943).

Books and Chapters

Darden, Robert. “The Sit-Ins.” In Nothing but Love in God’s Water, 11-22. Penn State University Press, 2017.

Meadow, Rosalyn, and Lillie Weiss. Women’s Conflicts about Eating and Sexuality: The Relationship between Food and Sex. New York: Haworth Press, 1992.

Parkin, Katherine J. Food Is Love: Advertising and Gender Roles in Modern America. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007.

Thiessen, Janis. “The ‘Romance’ of Chocolate: Paulins, Moirs, and Ganong.” In Snacks. Canada: University of Manitoba Press, 2017.

Websources

Naldini, Patrizia. “Bacchus by Caravaggio.” Uffizi Galleries. Accessed January 2, 2026. https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/caravaggio-bacchus

“Young Sick Bacchus by Caravaggio.” Borghese Gallery Rome. Accessed January 2, 2026. https://borghese.gallery/collection/paintings/young-sick-bacchus.html

Comments